For my analysis, I’ve chosen to examine Dunkin’ Donuts and Honeydew Donuts as a pair. Both companies sell donuts and coffee; both were founded & remained based in Massachusetts. Neither company is a particular favorite; after growing up on the airy delights that are yeast donuts, cake donuts land like moist hockey pucks.

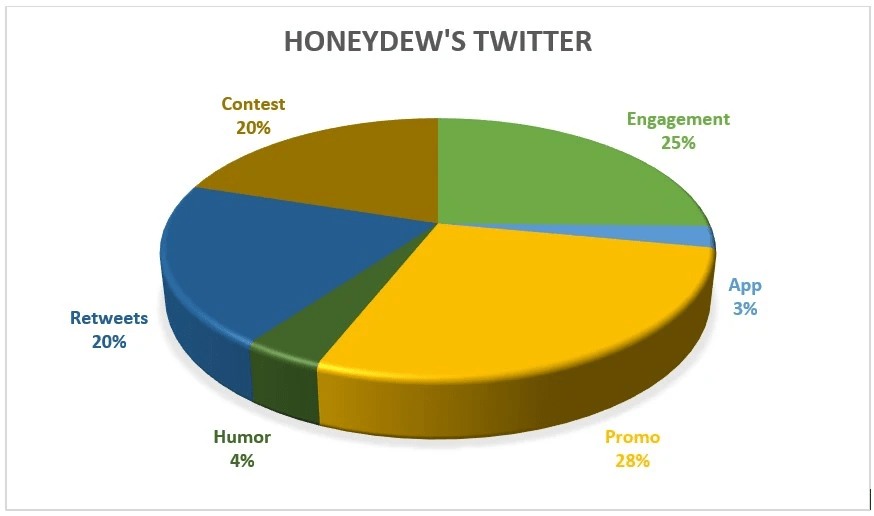

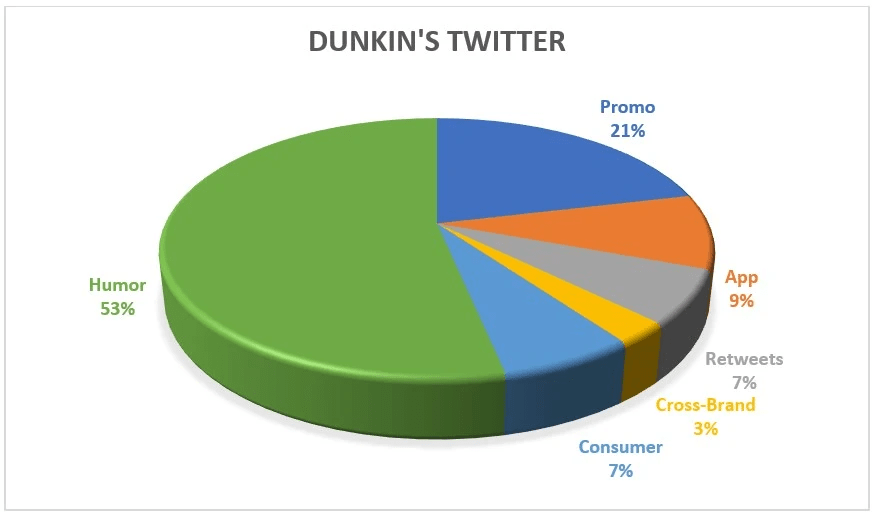

The coding for each company reveals a lot about their social media (SM) strategies. Dunkin’ relies heavily on humor as part of their SM strategy; while every post mentions Dunkin’ or their products in one way or another, Dunkin’s main goal appears to be millennial relatability. In contrast, Honeydew’s main SM strategy is product placement through promos and influencer engagement. While a few of their posts can be broadly defined as falling under the same idea of humor/relatability, Honeydew has invested much more of their SM strategy into brand development.

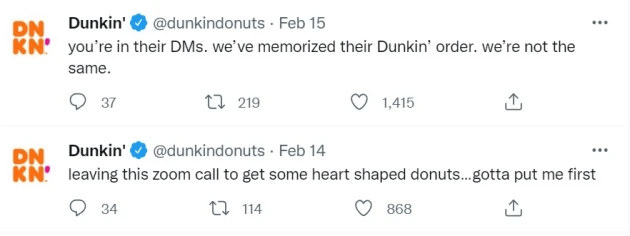

As mentioned earlier, Dunkin’ and Honeydew have a number of similarities. However, Dunkin’ is an international brand, whereas Honeydew is regional and found only within New England. This clearly affects their respective SM strategies. Dunkin already has strong market recognition, so they are able to spend a lot less time on product promos; they only seem to call out specific products, such as merch or salted caramel, because they are new and/or unusual. Instead, their SM account focuses on the use of humor as an avenue for building community. Most tweets, while they do reference Dunkin products, rarely have specific products to push. The “voice” of their Twitter account aims to create a “Dunkin’ lifestyle,” delivered in a light-hearted and engaging manner, with such tweets as “my first sip of Dunkin’ is a core memory for me.”

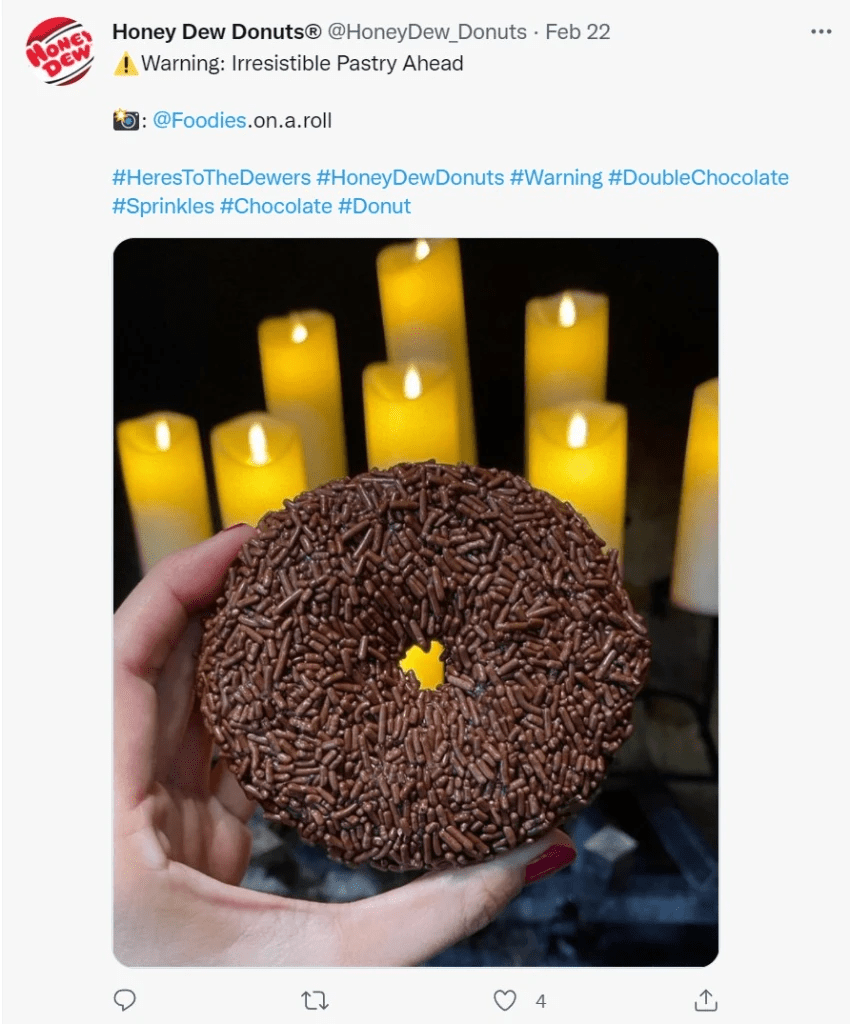

Honeydew, on the other hand, lacks the same brand recognition and must work to develop their brand’s online identity. Many of their tweets, whether it’s a photo posted by a Honeydew location or a Honeydew-affiliated influencer, reference specific products, such as a double chocolate donut or a hot coffee. The location tweets (where stores are mentioned by town) serve to reinforce specific locations, while the occasional retweet allow for community engagement. Another important means of community engagement for Honeydew is their “Dew Good” contest, which asked for “Dew Gooder” nominations from customers, who could nominate and vote for individuals who have a positive impact on their local communities.

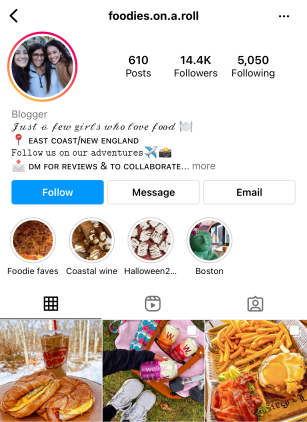

Honeydew engages in “social listening,” as described by Mary Lorenz, in ways that are more immediately obvious on their Twitter timeline than is the case for Dunkin’, who likely engage in more “behind the scene”-type listening projects. For Honeydew, this is particularly true with regards to brand management, which Lorenz describes as understanding “how audiences feel about their [brand] (what they love about it, what they don’t love, etc),” as seen in their current top post, which is an response to a January tweet from a customer who praised their breakfast sandwiches. Honeydew also engages in what Francine Charest et al describe as “3 Level Planning” – trust capital, attachment/transparency, and common cause (531). They build “trust capital,” their identity and reputation, with photos of actual in-store items. They also work on creating attachment through their reliance on SM influencers; the main influencer appears to be “foodies.on.a.roll,” who have an Instagram presence of 14.4k followers and who are located in New England. It’s not immediately clear that “foodies.on.a.roll” are paid collaborators; they are never identified as such on Honeydew’s Twitter account. However, further research uncovered their relationship when their Insta account was examined. Finally, Honeydew is engaged in the 3rd level of strategic planning, as described by Charest, et al, which is “common cause.” Honeydew, with their “Dew Good” contest, gave away $5000 to each winner (five in all) plus another $5000 to a charity of the winners’ choice. While this allowed them to engage with, and reward, members of their communities for having a positive impact, it also allowed Honeydew to build on their local brand recognition and reputation.

In contrast, Dunkin’s Twitter account exemplifies Charest’s 4Is: involvement, interaction, intimacy (affinity), and influence (532). Of these, “intimacy” is the most important; the account relies heavily on the “millennial relatability” posts earlier described. In so doing, Dunkin’ seeks to create a sense of affinity and intimacy among its followers; the centrality of Dunkin to New England life, for example, means that many of their New England-based followers feel a real affinity towards the idea of “when your Dunkin’ order is 98% of your personality.” This type of tweet also works towards involvement and interaction; every tweet invites a flood of responses – agreement, questions, critiques, and so on. The fourth I, influence, appears to be the weakest link on their Twitter page. However, they do have promos, occasional special app codes (which are quickly snapped up), and rare cross-brand engagement, all of which could be seen as a means of influencing their customers to respond to their tweets in very specific ways.

Of the two brands, Dunkin’s comes across as the more assured and professional; Honeydew’s Twitter account has some basic errors (such as not linking “foodie.on.a.roll” or other accounts properly) which leads to a conclusion that they are either inexperienced or oddly careless. These accounts, while ostensibly advertising much the same products, end up projecting very different SM strategies and personas.